The Problem: The homelessness crisis is worsening and imperils pregnant people and their infants.

On any given day, more than 560,000 people experience homelessness in the United States. Additionally, nearly 11 million households are severely cost-burdened — meaning they spend more than half their income on housing — and could be on the brink of homelessness. Compared to white people, Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color (BIPOC) are more likely to be homeless. Gender heavily influences housing access, stability, and opportunity, and yet, most housing justice data and legislation disregard misogyny and gender discrimination as a contributing factor. Women in the United States, especially women who identify as BIPOC face additional hurdles when trying to find and secure housing.

The multifaceted reasons people, and particularly women, experience homelessness are systemic and structural. They include, but are not limited to, a nationwide lack of affordable housing; a history, and current practice, of racist governmental policies such as redlining and blocking BIPOC families from affordable housing programs; and ignoring the needs of underserved communities such as formerly incarcerated people, survivors of domestic violence, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning (LGBTQ) youth.

The economic upheaval and explosion in unemployment from the COVID-19 pandemic have increased this risk. If the past relationship between unemployment and homelessness continues, there could be a 40 to 45 percent increase in homelessness this year, an addition of nearly 250,000 people.

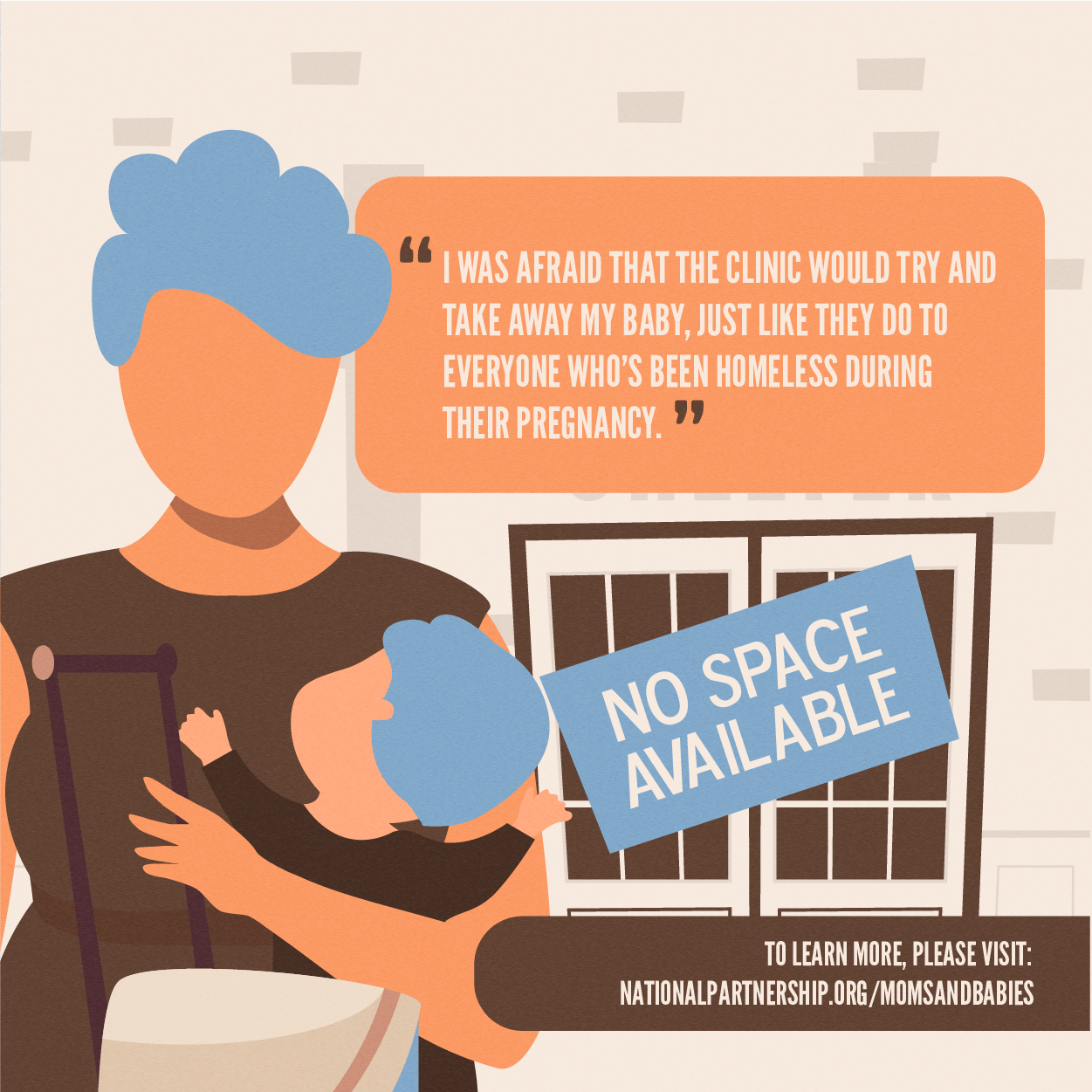

Access to stable housing has been identified as one the most important predictors of one’s health. People facing housing instability or who have fallen into homelessness have less access to health care. This is more pressing during pregnancy, a time when access to affordable, high-quality health care is crucial. Pregnant and parenting people experiencing homelessness face barriers such as lack of transportation and discrimination from health care providers. For some, these obstacles bar them from accessing care altogether. Additionally, people experiencing housing instability or homelessness are more likely to live in conditions that are hazardous to their health. The evidence is clear: Experiencing homelessness produces worse health outcomes for both pregnant people and infants.

Access to stable housing has been identified as one the most important predictors of one’s health. People facing housing instability or who have fallen into homelessness have less access to health care. This is more pressing during pregnancy, a time when access to affordable, high-quality health care is crucial. Pregnant and parenting people experiencing homelessness face barriers such as lack of transportation and discrimination from health care providers. For some, these obstacles bar them from accessing care altogether. Additionally, people experiencing housing instability or homelessness are more likely to live in conditions that are hazardous to their health. The evidence is clear: Experiencing homelessness produces worse health outcomes for both pregnant people and infants.

Homelessness Increases the Risk of Pregnancy Complications and Worse Health for Moms and Babies

A number of studies show that homelessness has a concrete negative impact on the health of pregnant people and their infants:

- Pregnant people experiencing homelessness are significantly less likely to have a prenatal visit during the first trimester, breastfeed their child, and have a well-baby checkup than their housed counterparts.

- In comparison with a housing-secure group with similar characteristics, pregnant people experiencing homelessness were significantly more likely to have various pregnancy-related conditions and complications, including high blood pressure, iron deficiency and other anemia, nausea and vomiting, hemorrhage (excessive bleeding), placental problems, and abdominal pain.

- One in five people who experienced homelessness in the year prior to giving birth had an infant with a low birthweight, a nearly 50 percent increase in risk compared to consistently housed people with otherwise similar characteristics.

- Newborn infants of people experiencing homelessness have longer stays in the hospital, and were more likely to require intensive care than infants of consistently housed people.

- People who were homeless as infants are more likely to have upper respiratory infection, other respiratory disease, fever, allergy, injuries, developmental disorders, and asthma, compared to people who were stably housed during infancy. They also have increased emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and health care costs.

BIPOC Communities and Women Disproportionately Experience Homelessness

Disparities in who experiences homelessness exacerbate the already large maternal and infant health inequities that plague BIPOC families. Unfortunately, the full impact of homelessness on moms and babies is unclear because of the lack of disaggregated, stratified data available by racial and ethnic subgroups. Nevertheless, evidence shows:

- Compared to white people, BIPOC communities are more likely to experience homelessness.

- Among all racial and ethnic groups, Pacific Islanders are the most likely to experience homelessness, with a rate nearly 14 times higher than white people.

- Native Americans are nearly six times more likely to experience homelessness.

- Black people are five times more likely to experience homelessness.

- Multiracial people are three times more likely to experience homelessness.

- Hispanic/Latino* people are nearly twice as likely to experience homelessness.

- Pregnant people experiencing homelessness are disproportionately Black, Hispanic, and younger.

- Black and Latinx renters, particularly women, are disproportionately threatened with eviction and actually evicted from their homes.

- During the COVID-19 pandemic, one in five renters were not caught up on rent, with BIPOC renters facing the greatest hardship, threatening their housing security.

- Black renters were three times more likely than white renters to not be caught up.

- Latino, Indigenous, and multiracial renters were nearly two and a half times more likely to not be caught up.

Recommendations

- Policymakers at the state, local, and federal levels must defend, strengthen, and enforce the federal eviction moratorium for the duration of the COVID-related eviction moratoria to prevent increased homelessness.

- Policymakers should invest more in housing models that have proven records of tenure security, such as community land trusts, limited-equity co-ops, and resident-owned communities.

- Congress must increase funding for the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Homelessness Assistance Grants program, which provides funding to communities that administer housing and services at the local level.

- Congress should pass the Social Determinants for Moms Act (H.R. 6132 / S. 346 Title I), part of the Black Maternal Health Momnibus, which would provide funding for state, local and tribal governments to increase access to affordable housing and wraparound services for pregnant and parenting people.

- State policymakers in the 12 states that have not adopted Medicaid expansion (Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Wisconsin, and Wyoming) should expand and target outreach and enrollment efforts to their homeless population.

- All state Medicaid programs should leverage 1115 waivers — which allow states to test new, innovative approaches in Medicaid — for housing supports and other services related to addressing adverse social determinants of health.

- Health care providers must provide culturally congruent maternity care for people experiencing homelessness, including training to recognize and eliminate any biases that may affect their treatment of these individuals. Additionally, providers should make referrals to programs that provide support for housing-insecure people as well as increasing access to care, such as offering extended hours and flexible scheduling.

- Federal and state policymakers must mandate all health care providers, payers, and government entities to collect race, ethnicity, and gender data (including subgroups) in consistent ways, and at sufficient levels of granularity, in order to effectively identify health and health care inequities and facilitate health equity analyses and policy development.

* To be more inclusive of diverse gender identities, this bulletin uses “Latinx” to describe people who trace their roots to Latin America, except where the research uses Latino/a and Hispanic, to ensure fidelity to the data.