The Problem: Health care and support for pregnant people with substance use disorder are inaccessible and inequitable, and instead they are shamed, stigmatized, and punished.

Maternal substance use disorder (SUD),* the chronic abuse of any drug or alcohol during pregnancy, is widely recognized as a significant public health and criminal justice issue. SUD can harm the health of pregnant and parenting people,** and their infants. Moreover, pregnant people and their families suffer because the systemically racist U.S. justice system’s punitive drug policies are disproportionately enforced against people of color. For example, compared to their white counterparts, Black and Latinx *** women with opioid use disorder (OUD) are 60 to 75 percent less likely to receive or to consistently use any medication to treat their OUD during pregnancy. Policymakers, health and social service providers, and researchers must reduce barriers to equitable care and focus on the voices of people of color to improve maternal and infant health outcomes.

Women, especially Black, Indigenous, and other women of color, often turn to substance use as a coping mechanism to relieve the distress stemming from unaddressed childhood trauma and ongoing discrimination and stigma rooted in centuries of systemic racism and injustice. In the absence of access to mental health services, many women turn to self-medicating with illegal substances or misusing prescription opioids for conditions such as anxiety. Women are most at risk of developing a SUD during their reproductive years (18–44 years) and as a result, pregnant people or people who may become pregnant are especially vulnerable to SUD.

Nicotine, alcohol, cannabis, opioids, and cocaine are the most often used drugs in the prenatal period. SUD can cause many health problems for pregnant people and their babies, both during pregnancy and postpartum, such as preterm birth and low birth weight. In the past decade, the prevalence of maternal SUD and subsequent pregnancy complications in the United States has increased dramatically. In fact, the national prevalence of maternal OUD more than quadrupled from 1999 to 2014. From 2007 to 2016, 7 percent of mothers who gave birth in hospitals had SUD diagnoses.

Nicotine, alcohol, cannabis, opioids, and cocaine are the most often used drugs in the prenatal period. SUD can cause many health problems for pregnant people and their babies, both during pregnancy and postpartum, such as preterm birth and low birth weight. In the past decade, the prevalence of maternal SUD and subsequent pregnancy complications in the United States has increased dramatically. In fact, the national prevalence of maternal OUD more than quadrupled from 1999 to 2014. From 2007 to 2016, 7 percent of mothers who gave birth in hospitals had SUD diagnoses.

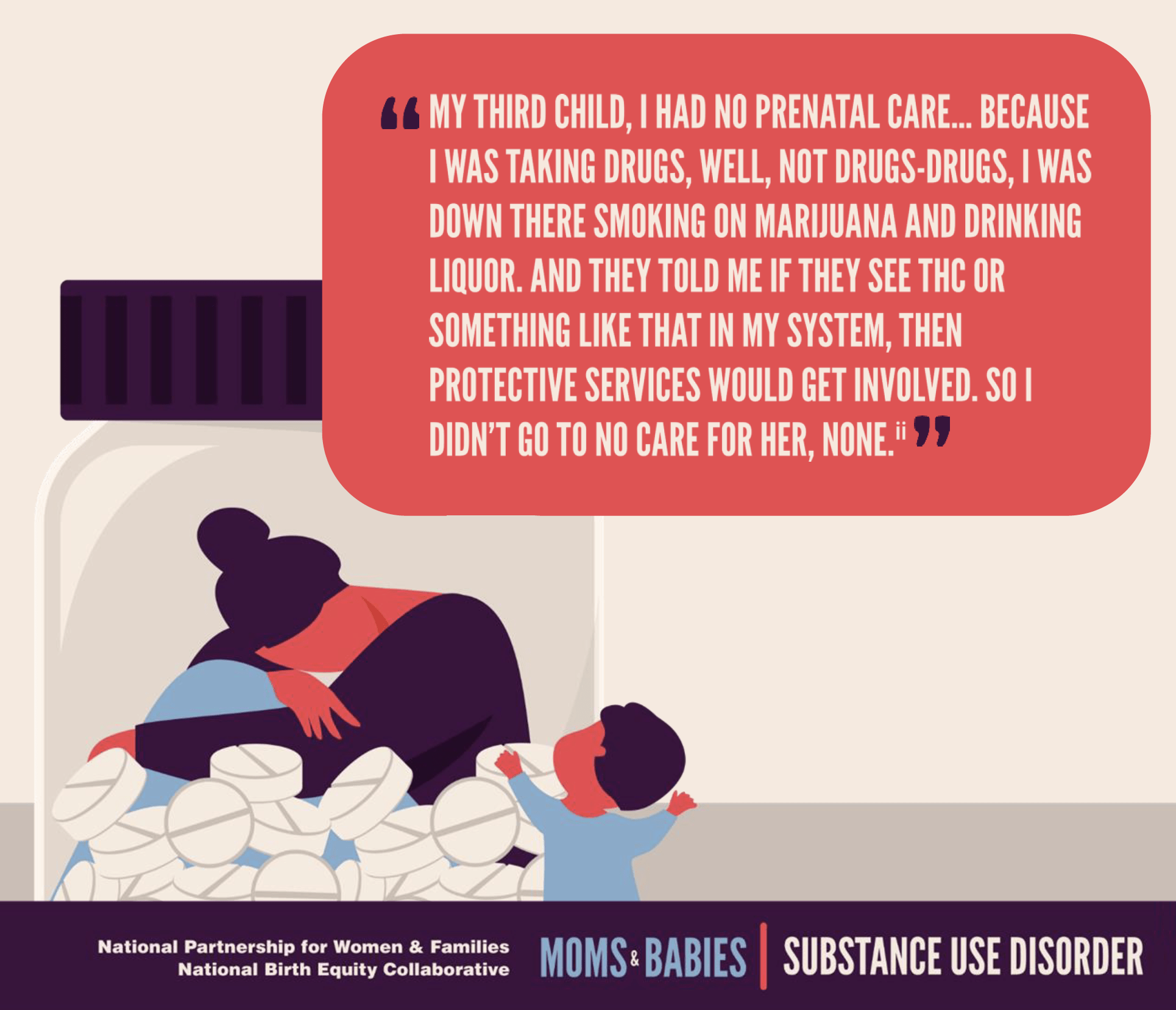

As a result, policymakers have responded by enforcing punitive laws. From 2000 to 2015, the number of states with punitive policies and requirements for health professionals to report suspected prenatal drug use more than doubled. These approaches however, have been found to instead cause poor health outcomes, such as higher rates of neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) – a drug withdrawal syndrome that occurs after infants are exposed to certain drugs in utero. The criminalization of substance use during pregnancy drives fear in pregnant people, resulting in fewer women seeking prenatal care and SUD treatment, which can ultimately endanger the health and well-being of mothers, infants, and their families.

Substance Use Disorders Present Myriad Health Challenges for Mothers and Babies

Systematic reviews (rigorous reviews that collect, assess, and synthesize the best available evidence from existing studies) have found:

- OUD during pregnancy is associated with preterm birth, small for gestational age (estimated fetal weight), lower birth weight, reduced head circumference, sudden infant death, and NAS.

- Alcohol consumption during pregnancy increases the risk of miscarriage, and surviving infants are more vulnerable to organ abnormalities and impairments in healthy development.

- Women, especially pregnant women, who smoke tobacco are more likely to experience stillbirth, neonatal death, and perinatal death compared to women who do not smoke tobacco.

- Fetuses exposed to cannabis are more likely to suffer low birth weight and need placement in the neonatal intensive care unit compared to infants whose mothers do not use cannabis during pregnancy.

- Pregnant women who use cannabis have increased odds of suffering from anemia compared to pregnant women who do not use cannabis.

Other individual studies have found that:

- Pregnant people with SUD, particularly those with opioids, amphetamines, and cocaine use disorders, are at greater risk of severe maternal morbidity, including conditions such as eclampsia, heart attack or failure, and sepsis.

- Between 2000 and 2014, there was a 26 percent overall increase in maternal mortality across the United States, particularly due to a rise in substance misuse and subsequent overdose among pregnant and postpartum people.

- Women with a history of recurrent substance use throughout their lifetime are more likely to develop postpartum mental health disorders compared to women who have not used substances throughout their lifetime.

- SUD increases risk of stillbirth and infant mortality and congenital anomalies.

- Infants exposed to substances in the womb are at greater risk for: developing NAS; impaired physical growth, development, and health; poor cognitive functioning and school performance; and emotional and behavioral problems, psychiatric disorders, and eventually SUD later in life.

- Interventions like breastfeeding, rooming-in, and remaining in close contact with babies rather than being apprehended by child protective services, reduce the need for pharmacotherapy for newborns with NAS.

- Many women with SUD are reluctant to receive routine prenatal care, or forgo it entirely, due to feelings of guilt, fear of losing custody of their children, and lack of transportation.

- Babies who do not receive proper prenatal care are more likely to suffer from preventable diseases, prematurity, congenital anomalies, and even infant mortality.

Black, Indigenous, and Other Communities of Color Face Distinctive Challenges Associated with Maternal Substance Use, Treatment, and Prenatal Care

Navigating a SUD, including diagnosis and treatment, is significantly more challenging for Black, Indigenous, and other people of color. The effects of maternal substance use exacerbate racial inequities in maternal and infant health outcomes.

- Black mothers with SUD are likely to feel discouraged from seeking care due to historical distrust of the health care system.

- Black mothers are more likely than other mothers to be reported to child welfare authorities by pediatricians and obstetricians suspecting prenatal drug use. Child custody loss due to maternal substance use has negative health implications for Black mothers, including increased drug use and mental health issues.

- Indigenous women suffer from higher SUD rates compared to other racial and ethnic groups because of experiences with emotional, psychological, and physical trauma related to colonialism, displacement, and loss of culture. They are also disproportionately affected by criminalization laws on the federal, state, and tribal level due to their race, socioeconomic status, and limited access to SUD treatment.

- Consistent use of medication for OUD treatment (defined as buprenorphine or methadone) during pregnancy is significantly lower for women of color. Deterrents may include punitive policies, racial discrimination by clinicians, cultural differences around medication use, perceived stigma of drug use during pregnancy, and minimal social supports.

- In 2018, only 23 percent of substance abuse treatment facilities offered programs specifically designed for pregnant and parenting women. Black and Latinx communities have substantially lower access to mental health and substance use treatment services.

Recommendations

- Congress must pass the Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act, which includes a suite of 12 bills to address the ongoing maternal health crisis, including legislation to:

- Support moms with maternal mental health conditions and substance use disorders.

- Make critical investments in addressing social needs.

- Provide funding to community-based organizations.

- Grow and diversify the perinatal workforce to ensure culturally congruent maternity care and support.

- Federal, state, and local governments must enact and enforce legislation that protects pregnant people with SUD from criminal charges and incentivize access to treatment and care without fear of judgment, incarceration, child removal, and other legal repercussions.

- Policymakers must expand access to substance use disorder treatment for pregnant and parenting women.

- Policymakers in states that have not yet adopted Medicaid expansion must take up the financial incentives passed in the American Rescue Plan Act to expand Medicaid eligibility. States should also take up this bill’s option to extend postpartum Medicaid coverage for 12 months.

- Federal policymakers should make 12-month postpartum coverage a permanent mandated Medicaid benefit.

- Federal, state, and local policymakers must urgently advocate for the care of pregnant people with SUD that prioritizes prevention, ensures access to prevention and treatment services, respects patient autonomy, provides culturally- and trauma-responsive and comprehensive care, and safeguards against discrimination and stigmatization.

- Policymakers and health industry leaders must make efforts to reduce explicit and implicit bias endemic in the health care system. As a bare-minimum first step, implicit bias training must be required by all health professionals and staff. There should also be performance measures and data collection to assess progress and effectiveness.

- Policymakers must encourage, and health providers must engage in, responsible opioid prescribing to women of reproductive age, without exacerbating well-documented racial and gender inequities in pain management – such as providers’ mistrust of patients’ reporting of pain and labeling it as “drug-seeking behavior.”

- Researchers must focus on the voices of women of color to affirm their priorities and preferences, and to identify promising avenues for future research and policy development.

* Substance use disorders occur when the recurrent use of alcohol and/or drugs causes clinically significant impairment, including health problems, disability, and failure to meet major responsibilities at work, school, or home.

** We recognize and respect that pregnant, birthing, postpartum, and parenting people have a range of gender identities, and do not always identify as “women” or “mothers.” In recognition of the diversity of identities, this series prioritizes the use of non-gendered language where possible.

*** To be more inclusive of diverse gender identities this bulletin uses “Latinx” to describe people who trace their roots to Latin America, except where the research uses “Latino/a” and “Hispanic,” to ensure fidelity to the data.