Of the numerous economic trends filling column inches over the last few years, few have gained as much traction as the “vibecession.” Coined by Kyla Scanlon in July 2022, the term refers to the phenomenon of people feeling “meh” about the economy despite positive traditional measures of economic health. Much digital ink has been spilled on the topic, including many recent articles declaring the vibecession has moved from hot in 2023 to not in 2024 as consumer sentiment has rebounded in recent months.

But whose feelings have been driving the vibecession in the first place? In a word, men’s.

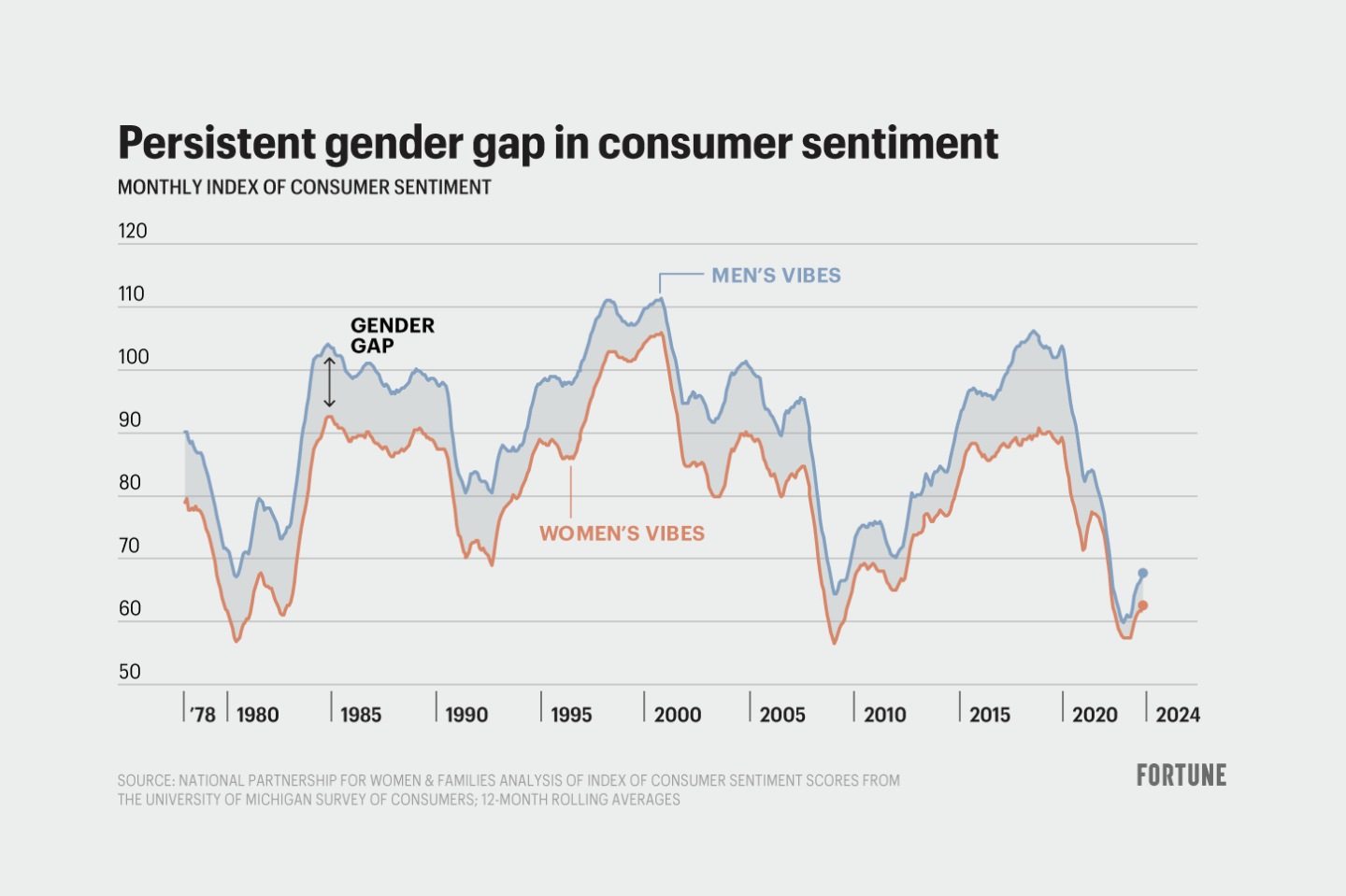

Men have nearly always felt sunnier about the economy than women have. Our research shows that in the 46 years of the University of Michigan’s monthly Survey of Consumers, men have felt worse than women about the economy just 15 times. While consumer sentiment has been down across the board since the pandemic began, our analysis also shows that a notable, yet undiscussed, aspect of the vibecession conversation was a substantial narrowing of the gender gap between how men and women feel about the economy. The vibecession was not just about everyone feeling bad about the economy – it was also about men finally feeling the same way as women do.

The economy still caters to the wants and needs of men

It’s not hard to imagine why women have been historically pessimistic about the economy. Women were only guaranteed financial autonomy via the right to open bank accounts or apply for credit or loans in 1974, shortly before the survey began. Through the latter half of the 20th century, women frequently faced unequal and hostile conditions on the job. The Supreme Court did not recognize sexual harassment as sex discrimination in the workplace until 1986 – within the lifetime of elder millennials. Women also continue to be forced to juggle work and caregiving, with the only national law explicitly focused on helping people balance these demands, the Family and Medical Leave Act, having been on the books for just three decades.

These legal and policy advancements helped make the economy work better for women – and the vibes certainly reflect that. Women’s consumer sentiment was 12.5% lower than men’s in the 1980s. By the 2000s, that gap was 10.2%. Over the last two years, it stands at 5.7%. But the truth of the matter is that the economy still caters to the wants and needs of men. It’s why almost half of all new businesses are started by women, but less than 2% of all venture capital dollars go to women-owned businesses. It’s why billions have been sunk into all manner of artificial intelligence startups largely founded by men, but the childcare workforce has barely recovered from COVID-19. It’s why women continue to be paid 78 cents for every dollar paid to a man and the gaps for women of color are worse.

It’s 2024. We have robot vacuums, phones switch on at a look, and tourists in space. Yet we still live in a society that expects women to work full time while also being full-time caregivers to children and aging parents with minimal support. The persistent gender gap in vibes reflects this impossible bind.

What if, instead of paying attention only when men are feeling as badly about the economy as women are, we focus on policies that lift women’s vibes? For instance, the gap narrowed during the vibecession because women’s perceptions of the economy improved substantially more than men’s in early 2021. What were women reacting to? It’s possible the passage of the American Rescue Plan Act, with its expanded child tax credit, child care rescue funding, and other key family supports buoyed women’s enthusiasm for future financial stability after so many were forced to make painful choices between caregiving and paid work during the first year of the pandemic. Though we can’t say for sure, this seems plausible to us and others given the popularity of these programs, especially for women.

Men’s and women’s vibes moved more or less in tandem throughout 2022, the “vibecession” era, and the overall vibes hit their nadir in June 2022, also the month of highest inflation and the lowest level of consumer sentiment ever recorded for men. The gender vibes gap then grew again in 2023. What happened in 2023? The dissolution of much of the hastily constructed social safety net assembled during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic and workplaces increasingly returning to “normal” – a normal that never worked well for women. And even though we can’t parse the vibes by race or disability status, experience from other analyses suggests women of color and disabled women are struggling mightily to stay afloat in a system and country that were built to exclude them twice and thrice over.

To be clear, focusing on consumer sentiment has been a much-needed shift in how we think and talk about the economy. But turning away from this conversation as the gender vibes gap has resurged is concerning. While many excellent journalists have written about moms’ struggles finding child care or the mental load of balancing work and family responsibilities, those discussions are rarely front and center in the economic conversation.

Women are more than half the population, almost half the workforce, and drive consumer spending – but how they feel about the economy hasn’t been a central part of the conversation. That has to change.

This piece originally appeared on Fortune.com.