Statement of Jocelyn Frye, President of the National Partnership for Women & Families WASHINGTON, D.C. – June 28, 2024 – Today, the Supreme Court upended sound, longstanding, legal precedent that has provided protections for everyday people for decades...

Improving Our Maternity Care Now

Download

The Strong Start for Mothers and Newborns Initiative was a federal five-year, multi-site project to test and evaluate enhanced prenatal care interventions for women enrolled in Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) who were at risk for having a preterm birth. One of the first Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation initiatives, it launched in 2012 to test three models of enhanced prenatal care among Medicaid beneficiaries: birth centers, group prenatal care, and maternity care homes. Midwifery-led care in birth centers generated stellar results, whereas results of the other two care models were underwhelming.

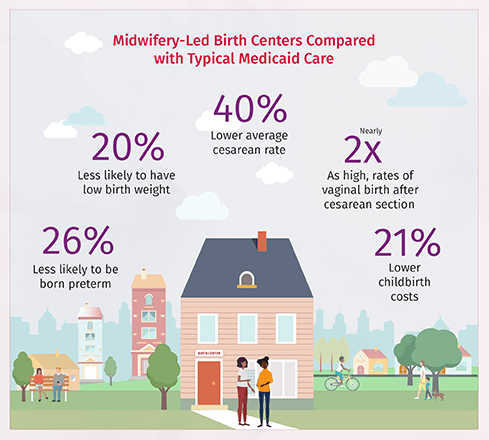

An independent evaluation compared women and infants in the midwifery-led birth center group with matched and adjusted women receiving typical Medicaid care in the same counties. The differences in outcomes between these two groups were compelling:

- Birth center infants were 26 percent less likely to be born preterm (6.3 percent versus 8.5 percent).

- Birth center infants were 20 percent less likely to have a low birth weight (5.9 percent versus 7.4 percent).

- The average cesarean rate in birth centers was 40 percent lower (17.5 percent versus 29.0 percent).

- Rates of vaginal birth after a cesarean at birth centers were nearly twice as high (94 percent more likely: 24.2 percent versus 12.5 percent).

- Childbirth costs at birth centers were 21 percent lower ($6,527 versus $8,286).

- At birth centers, total childbirth and post-birth costs up to one year after birth were 16 percent lower ($10,562 versus $12,572).

All of these are statistically significant advantages favoring birth center care. They include the many participants who received birth center prenatal care and gave birth in hospitals, either by choice or because protocols dictated a higher level of care.

In addition, Strong Start results were exceptional in reducing racial inequities. There were no differences by race for rates of cesarean birth and breastfeeding, or for the experience of care. Notably, participants reported feeling heard, being able to understand communications with the care team, having time for questions, being involved in decision-making, and being treated with respect.

The midwifery-led birth centers succeeded in providing benefits to families, the health system, and taxpayers by improving a series of fundamental health outcomes relative to usual approaches to maternity care. Given that Medicaid covered 42 percent of the nation’s births in 2020, including 66 percent of American Indian or Alaska Native, 64 percent of Black and 58 percent Hispanic births, advancing this model for Medicaid enrollees at lower medical risk could significantly mitigate our nation’s inequitable maternal and infant health crisis.

Back to Improving Our Maternity Care Now Through Community Birth Settings